After decades of mass immigration, European New Zealanders now make up less than 56% of the population and are on track to becoming a minority, the ethnic Maori population is now outnumbered by Asians, and Singh is the most common baby surname.

In a white paper released on his Substack last week and republished below with permission, public policy professional William McGimpsey looks at New Zealand’s immigration policy over time and the resulting national security, social cohesion, economic and civil rights issues.

McGimpsey then examines countries such as Japan, Israel and Hungary which have successfully implemented restrictionist immigration policies, and lays out 11 policy recommendations to solve New Zealand’s current mass migration-driven economic and social problems.

Introduction

This paper is about immigration policy in New Zealand. It identifies our current immigration policies as a key problem for New Zealand’s economy and society, and argues for significant reductions in immigration levels and changes in the types of immigrants brought in.

Background

Immigration policy has taken centre stage in public policy debates in the developed world over the last decade. In fact, some might argue we are experiencing something of a paradigm shift, or at least a prolonged period of intense debate between the liberal policy consensus (if that is the correct term) of the past half century, which advocated for relatively open borders and free movement of people, and advocates of a more restrictive approach aimed at preserving traditional cultural identities and social cohesion.

This debate has formed a key part of a series of highly contested and controversial political battles: including the Brexit referendum in the UK, the election of Donald Trump as US President, and the growing popularity of right-wing populist parties in Europe, such as Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, Germany’s AfD, and many others across the continent.

The immigration debate has perhaps been more subdued in New Zealand throughout this period, but there are signs of growing disquiet here as well, particularly given our rates of inbound immigration in recent years have been among the highest in the world (e.g. in the year to September 2023, New Zealand experienced 231,475 migrant arrivals, which is proportionally 4.4% of NZ’s population). Some commentators have begun to make the case that our immigration policies are contributing to significant public policy problems such as our housing crisis, infrastructure deficit, stretched public services, declining trust in institutions and flagging social cohesion.

Given that the New Zealand government has decided to eliminate diversity, equity and inclusion requirements within the public sector, it is timely to ask how much those imperatives also inform our immigration policy.

A note about immigration and free speech

Public discussion and debate about immigration policy is currently hamstrung, both within government and in broader society, by politically correct taboos around xenophobia and racism that make it difficult for the restrictionist position to be articulated and debated honestly without ad hominem attacks. The approach taken in this paper is simply to ignore political correctness and to state things as they really are.

A history of immigration in New Zealand

New Zealand is a relatively young nation and immigration has been vital in shaping the country’s identity, culture and economic prospects, but immigration policies have varied widely over New Zealand’s short history.

We can divide New Zealand’s immigration history three broad periods:

- The Establishment Period, 1840-1945 – Beginning from the founding in 1840 up until the end of World War II. In the initial period the focus was on bringing over immigrants from Britain and keeping out immigrants from other countries, particularly Asia.

- The Boom Period 1946-1974 – The focus in this period was on increasing New Zealand’s population – it had some of the fastest population growth in our history, the overwhelming majority of which was within the New Zealand European majority. However, during this period the groundwork was laid for the repeal of legislation that had been built up over previous decades to keep New Zealand majority White.

- The Replacement Period 1974-present – In this phase New Zealanders began leaving in sustained larger numbers. Liberalisation of immigration policy meant that immigrants became increasingly non-British and non-White, and the immigration rate for these populations increased dramatically over the period, drastically changing New Zealand’s ethno-cultural makeup.

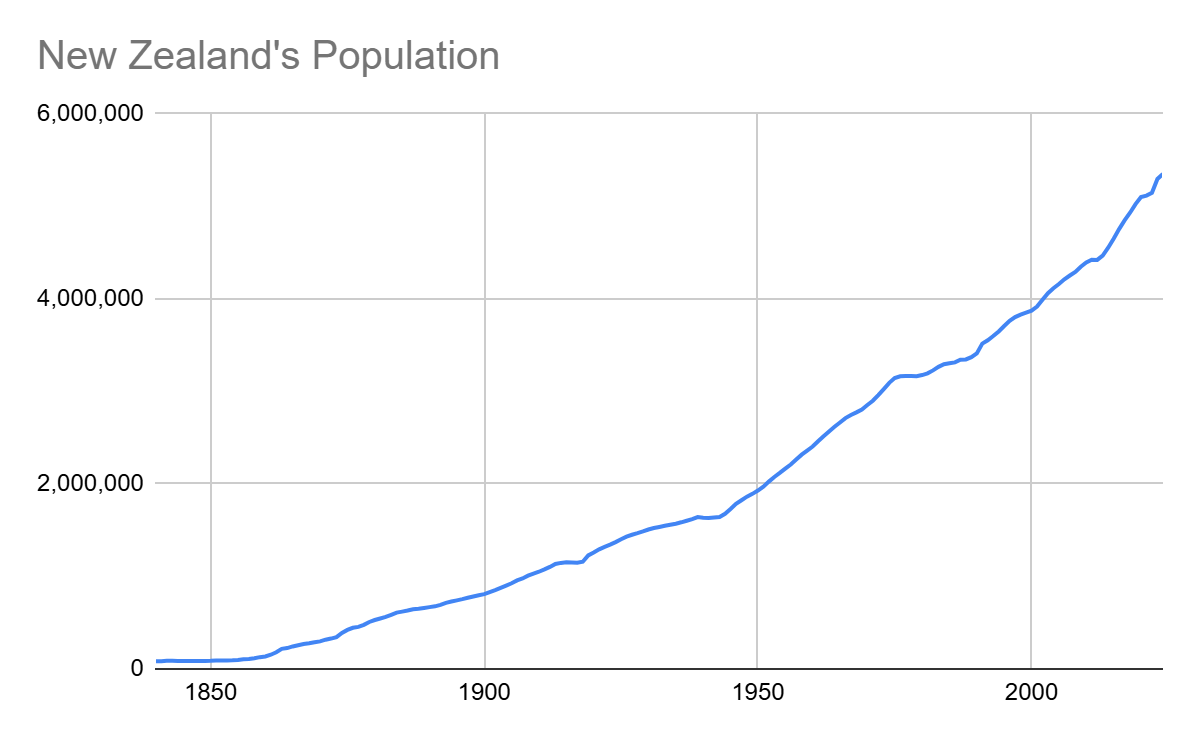

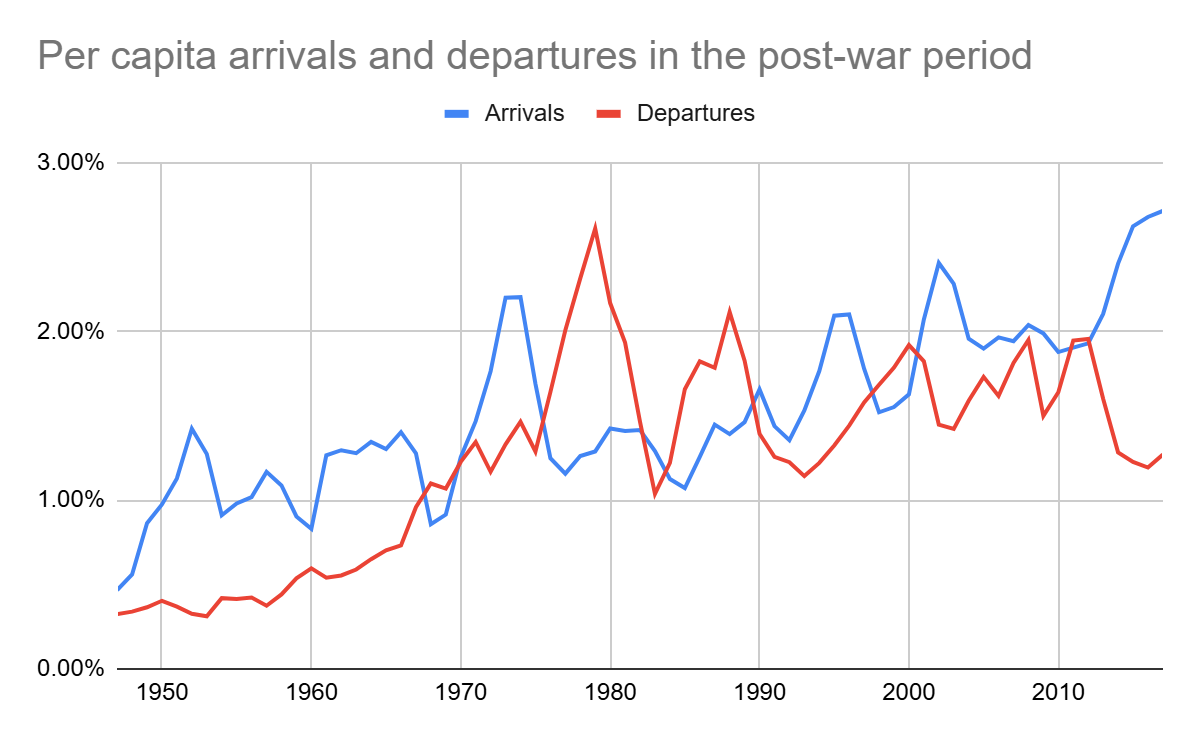

Figure 1: New Zealand’s Population

The establishment of the New Zealand nation 1840-1945

At the time of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi on 6 February 1840, the total population of New Zealand was around 82,000 people. Maori were the overwhelming majority, with numbers estimated at around 80,000, and European settlers estimated at 2000.

In the following decades, the British settler population increased significantly, aided by the gold boom and assistance provided by the provinces and the New Zealand Government. Between 1871-1891 the New Zealand Government provided assistance to British immigrants to come to New Zealand. In some years net immigration into the country ran at very high rates (because the population base – the denominator – was so small). So for example in 1865 New Zealand added a net 35,120 immigrants to its population, which reached 217,200 in that year, a per capita immigration rate of 16.2%, the highest in our history.

Figure 2: Per capita net migration and population growth rates

Government assisted immigration stopped after 1891, after which net migration stabilised at much lower rates and the population growth rate was relatively constant until after World War 2.

According to Stats NZ’s historical figures, over 300,000 people had migrated to New Zealand by the time of the 1901 Census, at which point the British settler population had reached 772,719 and the Maori population had fallen to 43,143 “full-blooded” and 5,540 “half-castes”.

The immigration laws passed in New Zealand during this period were focussed on limiting Chinese and Indian immigration to New Zealand and ensuring the population remained majority British – New Zealand passed no fewer than eight pieces of immigration legislation in this period with this aim.

By the end of World War II, New Zealand had reached a population of 1.7 million people, approximately 94% of whom were New Zealand European and 6% Maori.

The boom period 1946-1974

There was a marked acceleration in the rate of growth in New Zealand’s population after the end of World War 2.

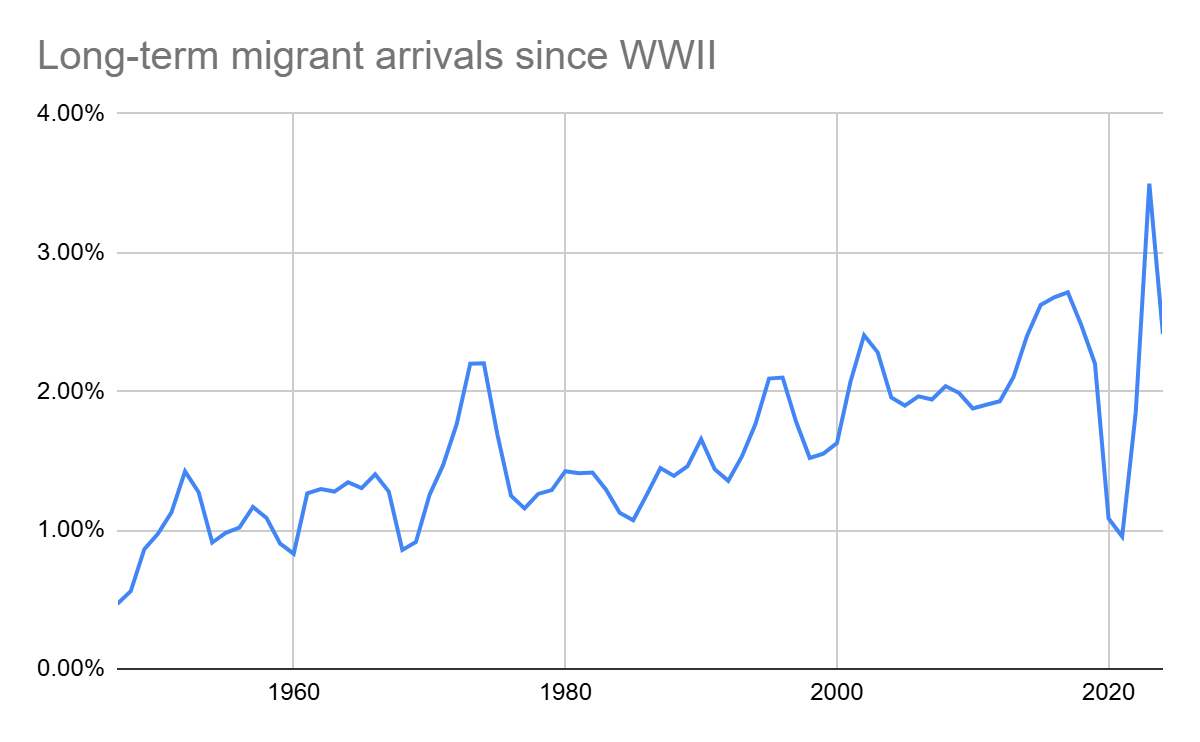

Part of this was relatively independent of net immigration: the baby boom, but in addition, there was a deliberate effort to increase the population via immigration. In 1946 a Select Committee investigation was established into how to increase New Zealand’s population. It concluded that natural population increase could meet most of New Zealand’s needs for a growing workforce, but that immigration would be needed as a supplement to fill skills shortages. Examining New Zealand’s rates of population growth, immigrant arrivals, and arrivals per capita, all three show a sustained acceleration during this period. In fact, the per capita rate of long-term migrant arrivals coming to New Zealand has continued to accelerate since the end of World War II.

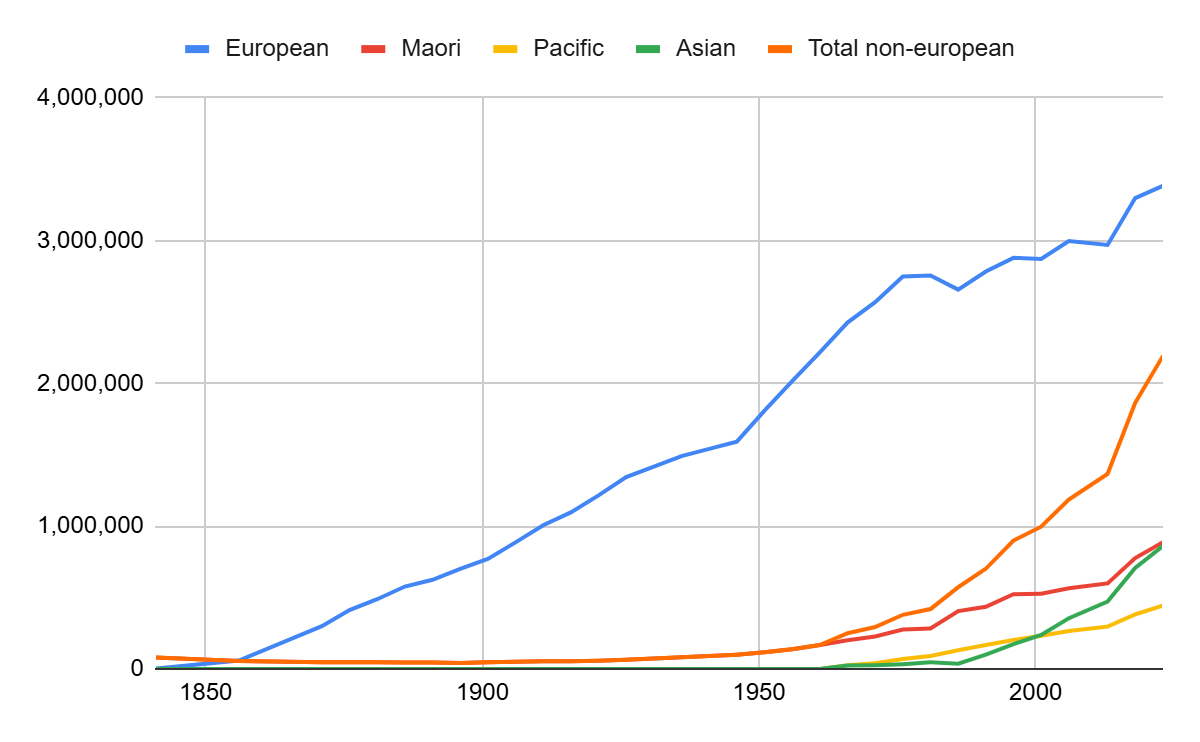

Figure 3: Long-term migrant arrivals per capita since World War II

As late as 1953 a memorandum from the Department of External Affairs still stated: “Our immigration is based firmly on the principle that we are and intend to remain a country of European development. It is inevitably discriminatory against Asians – indeed against all persons who are not wholly of European race and colour. Whereas we have done much to encourage immigration from Europe, we do everything to discourage it from Asia.”

However, during this period a few important pieces of immigration legislation were passed that laid the groundwork for New Zealand’s move away from our immigration system’s unofficial White New Zealand policy. The Immigration Amendment Act of 1961 and the Immigration policy review of 1974 led to British and Irish immigrants being required to have permits to enter New Zealand like people from everywhere else.

By the end of this period, New Zealand’s population had surpassed 3 million, nearly doubling in under 30 years. At this point New Zealand Europeans made up approximately 88% of the population, Maori had expanded to almost 9%, Pacific Islanders were 2% of the population and Asians 1%.

The replacement period 1974-present

The replacement period is when the unofficial White New Zealand policy was unravelled in earnest, and large-scale immigration from China, India and elsewhere began. The Immigration Policy Review of 1986 and Immigration Act 1987 abolished all the laws pertaining to race in New Zealand’s immigration policy that had been built up over the preceding century. It established three broad immigration categories: skills-based, family-based and humanitarian. Then the Immigration Amendment Act 1991 introduced our points system for the occupational category. These Acts were in effect revolutionary, and completely redefined New Zealand’s approach to immigration, putting the country on a path toward ever increasing ethnic diversity. These revolutionary changes continue to define New Zealand’s approach to immigration today.

As illustrated in Figure 3, there has been a steady increase in the per capita rate of long-term immigrant arrivals since WWII, from a rate of under 1%, it has steadily increased over the last 80 years to around 3%. This trend of arrivals slowly creeping up continued throughout the replacement period.

However, at the beginning of the period (the mid-late 1970’s), the population growth rate declined (see Figure 1), and stayed low through to 1990, with New Zealand experiencing a sustained period of net negative immigration, driven by a rise in departures. Kiwis left to seek greater opportunity as the oil shocks and economic stagnation of the mid-1970s dampened prospects at home.

In the early 1990’s net immigration turned positive again, coinciding with economic recovery and the implementation of the points-based immigration system. Although per capita long-term departures remained high during this period, our intake of long-term arrivals grew even higher as a result of revamped immigration policy.

Figure 4: Per capita arrivals and departures in the post-war period

However, the large numbers of Asian immigrants caused a mini-backlash in the mid-1990’s, leading to the 1995 immigration regulations which aimed to establish stronger English language requirements and give policymakers greater control over immigrant numbers. Reforms were attempted again in 2002/2003 changes, this time focussed on increasing both the English language proficiency and skills requirements. In neither case did these reforms do anything to change the ethnic composition of arriving immigrants. Despite these reform attempts, since the year 2000, New Zealand has experienced particularly high immigration rates. Looking at monthly data, the total long-term arrivals since the year 2000 have been just under 2.5 million. The population in the year 2000 was 3.8 million. This is simply an incredible level of population movement.

What we observe in terms of New Zealand’s immigration rates in the post-war period is a gradual increase in the per capita rate of people leaving New Zealand, but this is offset by an even larger increase in the per capita rate of new long-term migrant arrivals. Government policy does not directly control the number of people who leave, but it does directly control the number of long-term arrivals. Our immigration settings have socially engineered a population increase, in defiance of the decisions by New Zealanders themselves to leave, and radically reengineered the ethnocultural composition of the nation. We have essentially tried to replace the leaving Kiwis with Asian immigrants to ensure continued population growth.

Figure 5: New Zealand’s ethnic composition over time

Risks posed by our current immigration policies

Current immigration settings are focussed on driving population growth through large scale immigration and engineering a more ethnically diverse population. This section examines the risks these policies pose across multiple areas of public policy.

National security and geopolitical risks

Mass immigration and multiculturalism come with risks to social cohesion, strategic autonomy, and civil peace.

The geopolitical landscape of the 21st century is marked by increasing civilisational competition, rising ethnic nationalism, and the re-emergence of great power rivalry. In this context, the internal composition of a country becomes not merely a cultural question but a security concern.

Mass immigration, particularly when it involves large-scale intakes from culturally dissimilar or politically unstable regions, creates vectors for transnational influence, parallel loyalties, and social fragmentation. Multiculturalism, by rejecting assimilation to a shared culture and set of norms, can entrench these divisions, weakening the shared civic identity required for collective resilience in times of crisis.

History and recent events in Europe, North America, and even the Pacific Rim show that diversity can lead to ethnic enclaves with differing norms, increased identity politics, crime, terrorist attacks, and even violent conflict. This places governments in a catch-22 position where they are tempted to try and tamp down and manage these tensions by removing civil liberties like free speech and freedom of association, and increasing domestic surveillance of potential threats, which then exposes them to accusations of authoritarianism and civil rights abuses. This was the case in the US under George W. Bush with the introduction of the Patriot Act, under the UK’s Starmer government, during the recent uprisings over Axel Rudacabana’s killing of three little girls, and in Germany where the intelligence agencies are cracking down on AfD, Germany’s most popular party, due to it’s so-called “illiberal” policies towards immigration.

Mass immigration and multicultural policies can provide strategic footholds for foreign governments to exert influence through diaspora politics and information warfare. In a country like New Zealand, with a small population and limited defensive capacity, such vulnerabilities are magnified.

New Zealand’s intelligence and defence sectors have addressed security concerns related to immigration and multiculturalism, though they generally avoid framing these issues as direct threats (perhaps for reasons of political correctness). In August 2023 for example, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS) published an unclassified threat assessment that identified four key areas of concern, all of which are caused or exacerbated by our policies around large scale immigration and multiculturalism:

- Foreign Interference and Espionage: The report identified activities by foreign states aiming to influence or disrupt New Zealand’s national interests through deceptive or coercive means. These activities often target migrant and well-established communities, viewing them as potential dissidents. This interference extends to the political, academic, media, and business sectors.

- Violent Extremism: The NZSIS has reported concerns about individuals in New Zealand adopting extremist ideologies, some of which are influenced by international movements. While these ideologies are not exclusively linked to immigrant communities, the agency notes the global nature of such threats and the potential for individuals to be radicalized through online content.

- Transnational Organized Crime: The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC) has highlighted the risks posed by transnational crime, including drug trafficking and money laundering. These activities can be facilitated by established networks enmeshed in migrant communities.

- Social Cohesion and Disinformation: The NZSIS has expressed concerns about declining social cohesion. And have noted that individuals relying on discredited foreign information sources may be more susceptible to extremist narratives, which can lead to societal divisions.

Two recent examples are recent media reporting on Chinese influence and Sikh separatism.

There have been several media reports now of Chinese influence operations taking place within New Zealand. The existence of a sizable ethnic Chinese community in New Zealand makes it easier for agents of the Chinese government to find willing (or unwilling) accomplices, to camouflage its agents and activities, manoeuvre its people into positions of influence and so on. It also makes New Zealand more vulnerable to overseas influence operations designed to destabilise the country by nurturing and exploiting ethnic divisions.

The issue of Sikh separatism was raised in initial discussions the Luxon government had about negotiating a trade agreement with India – with the Indian side applying diplomatic pressure on New Zealand to crack down on Sikh separatists living here. Sikh separatist organisations are active in many Western Countries now – there have been recent media reports about their activities in Canada, the US and New Zealand. These groups are agitating for the establishment of a separate state – Khalistan – within India, which the Indian Government views as a threat to domestic security, and so is pressuring foreign government’s to crack down on their activities.

These examples illustrate how the existence of ethnic minorities in New Zealand makes it more likely New Zealanders will be asked to compromise their rights to free speech and political association, or submit to more domestic surveillance, in order to placate diplomatic, security or geopolitical concerns.

Risks to social cohesion

One of the key challenges of large-scale immigration is its impact on social cohesion. Immigration and diversity introduce complexities that can weaken trust and solidarity within societies. Research suggests that increased diversity can lead to reduced social trust, weaker civic engagement, greater societal fragmentation, and worsening socio-economic outcomes.

Robert Putnam and the threat to social cohesion

Robert Putnam, in his influential study E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-First Century (2007), found that ethnic diversity correlates with lower levels of social trust. His research, based on large-scale surveys across American communities, concluded that in more diverse neighbourhoods, people tend to “hunker down” – interacting less not only with those of different ethnic backgrounds but also with people from their own group. This decline in trust extends to reduced participation in community activities, weaker local governance, and lower levels of volunteering. Putnam explored the consequences of this in his book Bowling Alone. His thesis is that more diverse communities tend to have lower social trust and achieve poorer outcomes on all the normal socio-economic measures of well-being. This has since been verified by multiple studies.

Multiculturalism and Parallel Societies

The shift from assimilation-based immigration models to multiculturalism has further complicated social integration. When immigrant groups maintain distinct cultural, linguistic, and social practices without substantial interaction with the broader society, it can lead to the formation of parallel communities. These communities, rather than integrating, may develop separate institutions, media, and even legal norms (e.g. Sharia law), reducing the sense of national unity. Examples can be seen in parts of Western Europe, where enclaves with limited assimilation have contributed to social tensions and policy challenges, including debates over religious accommodations, language barriers, and differing social norms.

Declining Social Capital and Political Polarization

Beyond interpersonal trust, large-scale immigration-driven diversity can undermine social capital—the networks, norms, and shared values that enable cooperation in society. As Putnam and others have noted, declining social capital correlates with rising political polarization, lower institutional trust, and increased identity-based politics. In countries experiencing rapid demographic change, there is often a corresponding rise in populist or nationalist political movements, which reflect public concerns over cultural stability and national identity.

Challenges for Welfare States and Public Services

Social cohesion is also crucial for maintaining effective welfare systems. Historically, strong welfare states have depended on high levels of trust and a sense of shared identity among citizens. Studies have shown that in more ethnically diverse societies, there is often lower public support for redistribution and welfare policies, as people are less willing to fund social programs that benefit those perceived as outsiders (Alesina, Glaeser, & Sacerdote, 2001). This dynamic has been observed in the United States, where racial diversity has been linked to reduced support for public welfare programs.

Democratic legitimacy and free speech

As noted in the introduction to this paper, politically correct taboos around subjects involving diversity and race make it very difficult for a robust debate on the topic of immigration to even occur. This brings into question the democratic legitimacy of the immigration policy reforms that have been implemented in recent decades. These large changes to New Zealand’s immigration policies were undertaken without a democratic mandate – New Zealanders have never explicitly consented to the expansive multiracial policy that has been implemented through a referendum, and the restraints on speaking publicly on the subject resulting from political correctness mean they have never really had the full chance to be objectively informed on the subject, express their objections, or give informed consent through the democratic process.

Does mass immigration and multiculturalism violate civil rights?

Mass immigration of different peoples into a country arguably violates current citizens’ rights to self-determination.

The right to self-determination is a collective civil right recognised in Article 1 of the UN Charter and Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (an international agreement to which New Zealand is a signatory). It states:

1. All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

2. All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.

3. The States Parties to the present Covenant, including those having responsibility for the administration of Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories, shall promote the realization of the right of self-determination, and shall respect that right, in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations.

The right of a people to self-determination is foundational to international law and the rules based international order. It is a key part of the justification for why it is contrary to international law to interfere in the internal affairs of other nations or otherwise violate their sovereignty. It is also the key civil and political right that underlay the arguments against European colonialism. In fact, without the right of self-determination, there would be no compelling moral or legal justification for why separate nations ought to exist at all.

The argument that mass immigration violates the right of self-determination is that a people – i.e. a coherent ethnocultural collective – is not able to rule their own lands and set their own rules for their own communities if they have to share power, under a democratic framework, with other different peoples. This is very similar to the arguments made by leaders of anti-colonial movements in the mid-20th century.

French author Renaud Camus has gone so far as to describe the mass immigration in the latter part of the 20th century and early 21st century as a “Great Replacement” that involves a “change of people and civilisation” which he has described as “the crime against humanity of the 21st century”. Other commentators have referred to this phenomenon as “the suicide of the West” or “White genocide”.

Economic risks

There are also several economic risks resulting from large-scale immigration:

- It leads to housing shortages, infrastructure deficits and stretched public services.

- It depresses wages.

- It can contribute to lower productivity.

Mass immigration increases pressure on housing, infrastructure and public services

Some analysts claim that high rates of immigration place pressure on housing, infrastructure and public services.

A key economic concept that helps explain these phenomena is price inelasticity of supply – it is difficult, costly, and time consuming to build housing, infrastructure and increased capacity of public services. As a result, the quantity supplied of these things is relatively unresponsive to changes in price, which makes shortages and congestion more likely in the face of the large increases in demand brought about by immigration.

Inelasticity of supply can be caused by:

- Congestion effects – Public services, transport and infrastructure have fixed capacities in the short-run. If they are exceeded, it takes time and effort to increase the capacity.

- Capital formation lag – it can take time for investors or the government to recognise the need for investment and raise the capital necessary to provide the services.

- Fiscal strain and government budget constraints – Governments can sometimes struggle to make the fiscal outlays necessary to cope with high immigration inflows. This can be due to economic conditions (i.e. recession or high inflation), political constraints (a need to reduce spending and balance the budget), or poor planning.

In more concrete terms immigration increases population, and population increases increase the demand for housing, infrastructure and public services, leading to increased rents, housing shortages, and increased pressure on the capacity of our infrastructure and public services. The supply of homes is slow to adjust to rising demand due to zoning laws, construction time, and land availability. Sudden immigration surges can drive up rents and home prices. Roads, transport networks, and utilities require long-term planning and investment, making it difficult to quickly expand capacity. High immigration rates can result in overloaded systems. Healthcare, education, and welfare systems have limited resources. A rapid influx can strain them, lowering service quality for both immigrants and existing residents. Significant increases in supply of these services requires construction of new hospitals, schools and so forth, which takes time and is slow to adjust.

High rates of immigration depress wages

Governments often come under pressure from the business sector to allow more immigration to address “skills shortages”. The business sector’s complaints about skills shortages ought to be viewed in the same way as union complaints about unfair pay and conditions – i.e. it is often more about advocacy groups serving the interests of their members than bringing to light a genuine social problem. It is also a little ironic that staunch advocates of free markets would argue that central planning is needed to achieve optimal outcomes in the labour market.

The basic Econ101 level argument is that an increase of workers into the economy increases the supply of labour, which according to a conventional supply and demand analysis, would be expected to lead to a reduction in wages. This results from an elementary application of the law of supply, which is one of the first things taught in high-school economics classes.

However, for reasons both fair and foul, the consensus amongst economists for a long time has been that this relationship, which is fundamental in every other area of economics, does not hold in practice when it comes to immigration, due to:

- The fact that immigrants often work in different jobs and sectors of the economy, and so do not compete directly with domestic workers

- That immigrants can complement rather than replace native workers

- The dynamic effects of immigration on the economy – boosting demand as well as the supply of labour.

These caveats have come under increasing criticism in recent times, however.

New Zealand’s high rates of immigration may depress labour productivity

Wage growth in New Zealand has been hampered by our relatively poor labour productivity growth compared to other developed nations. This is a longstanding issue that has persisted for decades through both centre-left and centre-right governments.

One candidate explanation for this phenomenon is “The Reddell hypothesis”, proposed by New Zealand economist Michael Reddell. He argues that large-scale immigration into New Zealand has suppressed labour productivity by fuelling population growth without sufficient increases in capital, infrastructure, or high-value industries.

Reddell argues that New Zealand’s comparative advantage is largely in primary production (along with some other minor high productivity sectors), and that these industries don’t require a large labour force. Importing large numbers of people into New Zealand means diverting both labour and capital into less productive industries – such as housing and residential construction, public infrastructure, retail, hospitality and accommodation – thereby lowering average labour productivity and also preventing the economy from specializing or scaling our globally competitive industries.

In short, high immigration lowers productivity in New Zealand by misallocating resources and stretching limited economic capacity.

What about agglomeration effects?

Some economists have argued that there are economic benefits from “agglomeration”, and so New Zealand should grow its population through immigration to try and realise these benefits.

Agglomeration refers to an economic phenomenon where businesses and people cluster together in a specific geographic area, leading to productivity gains due to proximity. The idea is that being close together allows firms and workers to benefit from:

- Knowledge spillovers (learning from nearby firms)

- Shared infrastructure (e.g., roads, suppliers, services)

- Larger labour pools (firms can hire more easily; workers have more job options)

- Specialization (firms and workers can focus more narrowly, increasing efficiency).

However, given New Zealand’s small size and distance from key population centres, we are unlikely to achieve global competitiveness in the industries that benefit from these agglomeration effects, and so the push for more immigration based on these arguments merely leads to the bulk of the newcomers working in relatively uncompetitive low productivity industries. Given Auckland’s relatively low productivity compared to large cities in other countries, this argument seems plausible.

Reddell concludes that overall, rather than driving prosperity, New Zealand’s high immigration rates have contributed to low labour productivity, weak per capita income growth, and economic imbalances that have shifted resources away from industries in which New Zealand has a competitive advantage, preventing us from specialising and scaling them up.

Summary problem definition

New Zealand’s current immigration policies are harming its citizens:

- High rates of immigration are placing significant pressure on housing, infrastructure and public services, depressing wages, and hampering labour productivity growth.

- The policy of using the immigration system to deliberately increase ethnic diversity poses national security concerns, threatens social cohesion, and undermines New Zealanders rights to self-determination.

Alternative approaches

While the policies of mass immigration and multiculturalism have been adopted by many developed countries, there are several other successful examples of countries that have instead adopted more restrictive immigration policies and not fully embraced multiculturalism. This section sketches a few brief examples.

Japan

Japan maintains a highly restrictive immigration policy, with the goal of preserving ethnic homogeneity and its unique culture and national identity. The country has historically limited immigration, especially from non-Asian countries, and has stringent requirements for permanent residency and citizenship. Rather than using permanent migration as an economic lever, labour shortages are addressed through controlled temporary worker programs that require the workers to leave after a set duration. Japan has also historically accepted very few asylum seekers – only 303 people were granted refugee status in 2023 for example.

As a result of these policies, Japan has been able to maintain low crime rates, high levels of social trust, a strong national identity and cultural continuity.

South Korea

South Korea is slightly more open to immigration than Japan, it nevertheless maintains a selective immigration policy, primarily allowing temporary labour migration. The country emphasizes cultural assimilation and has limited pathways to permanent residency or citizenship for foreigners.

The goal of these policies is to address specific labour shortages in industries like manufacturing and agriculture, while preserving the nation’s cultural identity and social harmony, and ensuring national security and public safety. This has been largely successful, although there have been some challenges in integrating foreign workers and their families. Like Japan however, South Korea also suffers from an aging population.

Israel

Israel’s immigration policies aim to preserve the Jewish character of the state, promote Zionist nation-building, ensure national security and maintain social cohesion. The cornerstone policy is the Law of Return, which grants Jews (defined as individuals with at least one Jewish grandparent) and their spouses the right to immigrate to Israel and become citizens. Israel takes a stringent approach to immigrants and asylum seekers from Palestine, other Muslim and Arab countries and African nations, for reasons of national security and social cohesion.

These policies have been successful in preserving the Jewish character of the state, ensuring Jews remain the majority of the population, protecting national security and supporting social cohesion.

Hungary

Hungary, under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, has implemented strict anti-immigration policies, opposed multiculturalism and promoted a homogeneous national identity. The government has enacted laws to limit immigration, particularly from non-European countries and has been vocal against accepting non-European refugees.

The goals of these policies are to preserve Hungary’s national culture and Christian heritage, prevent demographic changes, enhance national security, and assert Hungary’s sovereignty over immigration policy in the face of EU directives. Orban has been explicit in his opposition to the activities of advocacy networks linked to George Soros’ and his Open Society Foundation which have sought to open Hungary up to immigration and progressive social movements.

Hungary’s policies have been largely successful, although they have been criticised by the European Union.

Poland

Poland has maintained a cautious approach to immigration, with a preference for cultural and ethnic homogeneity. Poland has been more open to arguments for accepting migrants in order to boost its economy than Hungary, although while it accepts migrant labour from neighbouring European countries, the government has been resistant to accepting refugees from non-European nations.

The goals of Poland’s immigration policies are to preserve national identity and cultural cohesion, address labour market needs through selective migration, and ensure national security and public order.

These policies have been largely successful although have resulted in criticism from the European Union over refugee policies.

Denmark

In recent times, Denmark has shifted its immigration policy focus from integration to repatriation, particularly for refugees. The government has implemented measures to limit immigration and encourage return to countries of origin.

In 2019, Denmark enacted a policy change known as the “paradigm shift”, no longer seeking to integrate refugees, but encouraging them to return as soon as conditions permit. This has led to a notable reduction in residence permits from 6,200 in 2021 to 1,400 in 2022.

Denmark also now offers financial support to migrants wishing to return. Eligible individuals can apply for a variety of payments ranging from approximately NZ$4000-$10,000; and they have implemented housing policies aimed at dispersing non-Western immigrant populations.

The goals of these policies are to maintain social cohesion and public trust, reduce the number of non-Western immigrants, and encourage integration through strict requirements. The policies have proven popular with Denmark’s citizens, aligning with changing public attitudes towards immigration.

Sweden

Sweden has also made significant shifts in its immigration policy away from its traditionally “liberal” approach to a more restrictive approach emphasising “remigration” – encouraging and facilitating the return of migrants to their countries of origin.

Sweden offers financial support to immigrants who choose to return to their home countries – SEK 10,000 per adult (approximately NZ$1,750) and SEK 5000 per child (approximately NZ$875 to up to a maximum of SEK 40,000 per family (approximately NZ$7,000). The Swedish Government intends to increase this up to SEK 350,000 (approximately NZ$61,000), in 2026, making it one of the most generous such programs in Europe. The policy aims to encourage voluntary departures, particularly among those who have struggled to integrate into Swedish society.

The government has also implemented measures to ensure that individuals with deportation orders leave the country. These include extending the validity of removal orders to five years from the date of departure and eliminating the possibility of applying for work permits from within Sweden after a failed asylum application.

Sweden has adopted the minimum allowable asylum standards required under EU law, reducing the number of people eligible for asylum. In 2024, Sweden granted the lowest number of residence permits to asylum seekers and their relatives since records began in 1985 – a 42% decrease since the current government took office.

Stricter requirements for citizenship, including longer residency periods, language proficiency, and knowledge of Swedish society have also been introduced.

These policy changes have led to a notable decrease in immigration and an increase in emigration, resulting in a negative migration balance for the first time in over 50 years. The shift has sparked public debate within Sweden, but in general aligns with recent shifts in public opinion over immigration.

Policy recommendations

Principles

More restrictive immigration policies that dramatically limit numbers and that prioritise ethnic, cultural and religious affinity rather than diversity are both desirable, and have been effective in other countries. This section outlines some specific policies New Zealand could implement to achieve similar goals.

At the principles level, we should aim for an immigration system that:

- Preserves social cohesion, by sourcing immigrants from culturally similar countries.

- Puts kiwi workers first by bringing in foreign labour only in genuinely highly skilled occupations where there are proven skills shortages.

- Places less demand on our housing, infrastructure and public services, by limiting overall immigration intake much more significantly than at present.

Specific recommendations

- An immigration moratorium

New Zealand’s immigration intake and the rate of demographic change within our society has been very high in the post-Covid era. A moratorium would allow the new arrivals time to either assimilate or leave (New Zealand has very high rates of immigrant turnover, many who come, leave again). This would give the social disruptions resulting from the excesses of our current immigration policies time to settle and give those immigrants wishing to stay time to assimilate.

- Cap annual immigration intake

In the longer term, annual immigration intake should be explicitly capped at a low level (10,000–20,000 new permanent residents per year for example). It is the number of migrant arrivals that should be capped, not “net immigration” – focussing on achieving positive net immigration unnecessarily bakes-in a policy of immigration-led population growth, for which there is no real justification and which has likely caused unnecessary economic harm and perverse economic incentives. Humanitarian exceptions could be excluded but eligibility tightened. Capping immigration at a lower level would slow the rate of demographic change and preserve social cohesion, while still allowing flexibility to meet genuine labour force needs.

- Limit future immigration to traditional and culturally compatible sources

Source countries should be limited to ensure the immigrants entering New Zealand are from culturally and linguistically similar countries and are familiar with how things work in our society. The focus should be on traditional sources of immigrants, and those who are more likely to fit in and assimilate. Appropriate countries that fit these criteria are the UK, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and the United States. Immigrants from the Netherlands and Scandinavia could also be considered, along with White South Africans. Small numbers of immigrants from our pacific neighbours could also be maintained – honouring our traditional and existing arrangements with these countries.

- Cultural Compatibility Assessment

Require immigrants to pass a cultural compatibility interview and test before approval of residency or citizenship, with the goal of ensuring integration and cultural alignment.

This would include requiring fluency in English language, and a test on New Zealand civics, history, and cultural values. Interviews should be conducted with immigrants to assess their intent to integrate, adopt New Zealand’s customs, work and contribute to the community.

- Temporary Work Visa Overhaul

The immigration system must be reformed to ensure that labour shortages and economic migration is provided for through temporary work visas rather than offers of residence.

These visas should then be restricted to genuinely essential industries, where a shortage of New Zealand workers has been empirically demonstrated. Strict employer obligations should be set.

The goal should be to end the pathway-to-residency via low-skilled temporary work. This could include requiring proof that no New Zealander is available, imposing time limits (e.g. max 2 years, with no path to residency). banning employer-sponsored family reunification and mandating contributions to a repatriation fund.

- Reform the Points System

Two important reforms of the points system are needed. First, the net has been cast too wide in recent years, with many of the immigrants brought in being low-skilled rather than high-skilled. Along with capping the numbers, the focus should be exclusively on highly skilled immigrants in professions where New Zealand has a verified shortage.

Secondly the skilled migrant category should also prioritise cultural affinity and civic alignment. Extra points should be given for English-speaking origin, education in New Zealand, or aligned cultural background. Points should be removed or reduced for age and family connections that dilute integration.

- Tighten Asylum and Refugee Pathways

Limit refugee intake to the UN minimum and impose cultural fit and skills assessments. This could involve prioritising European and Pacific Islander Refugees, Christians, and those with proven capacity to integrate. This should be accompanied by mandatory English training and job readiness.

Secondly, the refugees should be admitted on the understanding that their stay in New Zealand is temporary, and they are expected to return home again when conditions permit.

- Repatriation and Return Incentives

Offer financial and tax incentives for migrants who voluntarily return to their country of origin to gradually reduce the numbers of non-integrated migrants.

Many recent immigrants will return or move on (and in fact are already) without financial incentives – there is a high degree of “churn” in migrant arrivals and departures. But some migrants could also be encouraged to leave with incentives, especially when the incentives are likely to save the taxpayer money in other ways (through not having to fund deportations, welfare, treatment for drug use or addiction or possible jail time for example) – think of this as a “social investment approach” to remigration. The incentives could include funded return and reintegration grants, tax-free repatriation of savings, and voluntary renunciation of residency or citizenship.

Deportation should be automatic for migrants who commit crimes, especially involving violence, rape or sexual abuse, and corruption, after they are convicted. Deportation of foreign criminals should be either before or after serving sentences depending on if they can serve their sentences in their home country. Immigration New Zealand’s powers to detain and deport visa overstayers should also be broadened.

- Citizenship Reform

Citizenship should be made more selective, along the lines of the model of Israel or Japan. Israel is a fundamentally Jewish state, and Japan a fundamentally Japanese one, and grants of citizenship are made in order to preserve the nation-states basic ethno-cultural character and its social cohesion. New Zealand citizenship should be granted in order to ensure New Zealand remains Kiwi – i.e. retains its Anglo-Māori ethnocultural character.

Residency requirements could be increased from 5 to 10 years. Fluent English and full-time employment should be absolutely mandatory. A cultural test, interview, and public ceremony with oath of allegiance should be required. Automatic citizenship for children born in New Zealand to non-citizen parents should be removed.

- Ban on Foreign Religious and Political Influence

Prohibit funding or control of cultural, religious, or political institutions by foreign governments or entities, with the goal of preventing the development of parallel societies and foreign ideological influence. Foreign-government-funded mosques, schools, or media should be banned and all community and advocacy organisations should be locally governed and meet transparency requirements.

- Establish a Cultural Preservation Office

Establish a government office to monitor and report on the cultural effects of immigration. The office would be explicitly tasked with cultural preservation, and would be required to provide annual reports on immigration’s effects on demographic change and social cohesion. It would also have the authority to recommend changes to immigration policy.

Conclusion

For most of its history, New Zealand had an unofficial White New Zealand immigration policy.

After World War Two we made two important changes to our immigration policies which have likely harmed New Zealand economically and socially:

- We pursued a deliberate policy of immigration-led population growth.

- We dismantled the system of immigration laws designed to keep New Zealand ethnically and culturally homogenous.

The scale of immigration and ethnic and cultural diversity brought into New Zealand has accelerated in recent years, causing a persistent housing crisis, infrastructure deficit and stretched public services. Our national security, social cohesion, sense of national identity, and right to self-determination have also come under threat due to rapidly increasing ethnic, cultural and religious diversity.

In light of these facts, it is reasonable to ask whether the quantity and type of immigrants coming into New Zealand are really serving the country well. This paper concludes they are not, and in fact our immigration policy is causing significant problems.

In broad strokes, the solution is twofold:

- Significantly reduce the number of immigrants coming into New Zealand. There is no need to pursue a policy of deliberately growing the population through immigration. Immigration should be restricted to truly critical skills shortages only, and if more people choose to leave the country than the numbers coming in, that’s ok.

- Undo the changes made in recent decades that have made it a goal of the immigration system to promote ever greater diversity. Instead, return to the earlier policy of promoting ethnic and cultural homogeneity and cultural continuity. We should attract immigrants who are similar to New Zealanders – ethnically, culturally, religiously and linguistically. This would mean focussing on attracting highly skilled migrants from predominantly Anglosphere countries, while retaining our historic links and small flows of people from the pacific.

In addition, it is appropriate to consider policies and incentives to encourage recent immigrants who are ethnically and culturally dissimilar to New Zealanders, or who have otherwise struggled to integrate, to go home, to correct the problems arising from previous mistaken immigration policies.

Header image credit: Kerin Gedge on Unsplash.