Over the past week, Union Jacks and St George’s Crosses have begun appearing across England as part of an online campaign called “Operation Raise the Colours.” This trend caught my attention because, although the campaign invoked both flags, the Cross of St George seemed to be far more represented. A recent article in The Telegraph even asks “Is this the beginning of the English revolution?”

Seeing this mini-revival of the English flag, I was reminded of an old essay from the conservative philosopher Roger Scruton: England: an identity in question. Though it was years since I first read it, it always stuck in my mind because Scruton surprised me with his advocacy of English nationalism against the more civic, British identity.

Scruton explained how he too had noticed an English identity beginning to resurface beneath the British one among the majority population of the Union:

The desire for an English, as opposed to a British, identity is growing rapidly. When I was a teenager, crowds who supported England in football or cricket matches waved the Union Jack; now they wave the flag of St George. This flag is beginning to appear on suburban lawns and in rural farmyards, and the word “England” is increasingly heard in contexts where until a few years ago “Britain” would have been the norm.

In the essay, Scruton wrote sympathetically of pleas for Scottish independence, noting that the British government made a great mistake in resisting Irish demands for national independence in a way that led to unnecessary conflict and long-term enmity between the nations.

But it was what an island of independent nations could mean for his England that was his focus. Writing this in 2007, Britain’s 2005 General Election was still fresh in Scruton’s memory.

That election returned Tony Blair’s Labour to power in Britain, yet Scruton notes that the Conservative Party actually received more votes than Labour in England. However, Labour still secured a massive majority in parliament, largely due to the voting power of the Scottish and Welsh. This reflected a long-standing dynamic in British politics that continues to this day:

The Labour Party has always relied on those votes in order to secure its periods of office, knowing that the separatist feelings of the Celts readily lend themselves to the fight against the somewhat mythical, but still resonant, threat of the English Tory establishment. However, the strategy of using the Celtic vote to govern the English has depended upon keeping the Celts within the kingdom, which is why the Labour Party granted them some measure of independence, lest their grievances cause them to break entirely away.

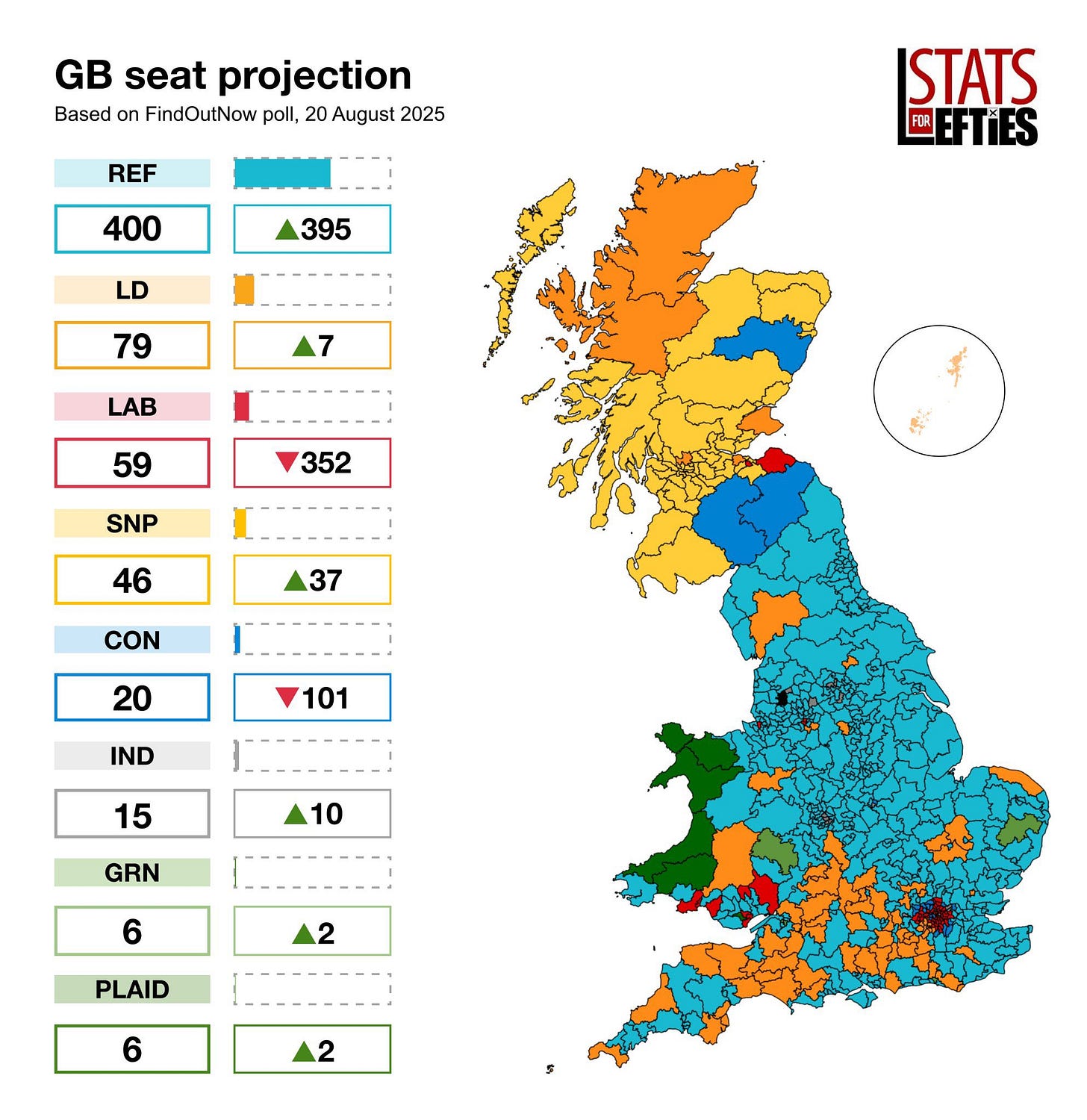

If there was a political division between the English nation and its Celtic neighbours in 2005, that division is far more stark now with the rise of Reform and the Scottish National Party. Just look at the seat projection for the British parliament if an election were to be held in 2025:

What jumps off the map is the extreme ethnic fragmentation. Putting aside how much Labour support relies on the large, multiracial metropolitan areas, it is clear that an England shorn of its union with Scotland and Wales would deliver an overwhelming majority to Reform. This will be the likely outcome of the next election anyway, but the fragmentation Scruton wrote about in 2007 is even stronger now.

So what are we to make of this mini-resurgence in English identification? Firstly, I believe the breakup of the United Kingdom in our lifetime is inevitable: a shared British identity is waning, the individual nations of the Union are more politically divided than ever, and voting trends point to a second Scottish independence referendum likely to succeed — after which Welsh demands for independence will reach a fever pitch.

This political fragmentation coincides with the decline of any meaningful shared British identity. As Britain has grown more multicultural and universal in its self-definition, “Britishness” has shifted from a rooted national loyalty to a vague civic label.

Scruton anticipated this shift. In his book “England And The Need For Nations”, he reflects on the trajectory of British identity. Drawing on a popular historian who described it as a politically constructed, imperial project, Scruton observed that:

The idea of a British national identity makes sense only because of the other and more deeply rooted identities that it subsumes. The Scots continue to describe themselves as Scots; the Irish as Irish—or, if they reject the Republic, as ‘Unionists’, meaning adherents to the strange legal entity described in their passports. The Welsh, who provided us with our most determinedly English kings, the Tudors, are still, in their own eyes, Welsh. The English remain English, and in their hearts it is England that secures their loyalty; not Scotland, Ireland or Wales. Only one group of Her Majesty’s subjects sees itself as British, but not English, Scottish, Irish or Welsh—namely, those immigrants from the former Empire who have adopted British nationality while retaining ethnic and religious loyalties forged far away and years before. Many of our fellow citizens are ‘British Pakistanis’, while ‘English Pakistani’ suggests someone of English descent resident in Pakistan, rather than a Pakistani immigrant to England.

…

The British experience therefore illustrates the way in which a composite national identity can be forged into a single jurisdiction, while also providing shelter to minorities who may as yet have no national loyalty at all but whose children, it is hoped, will be brought up to acquire one.1

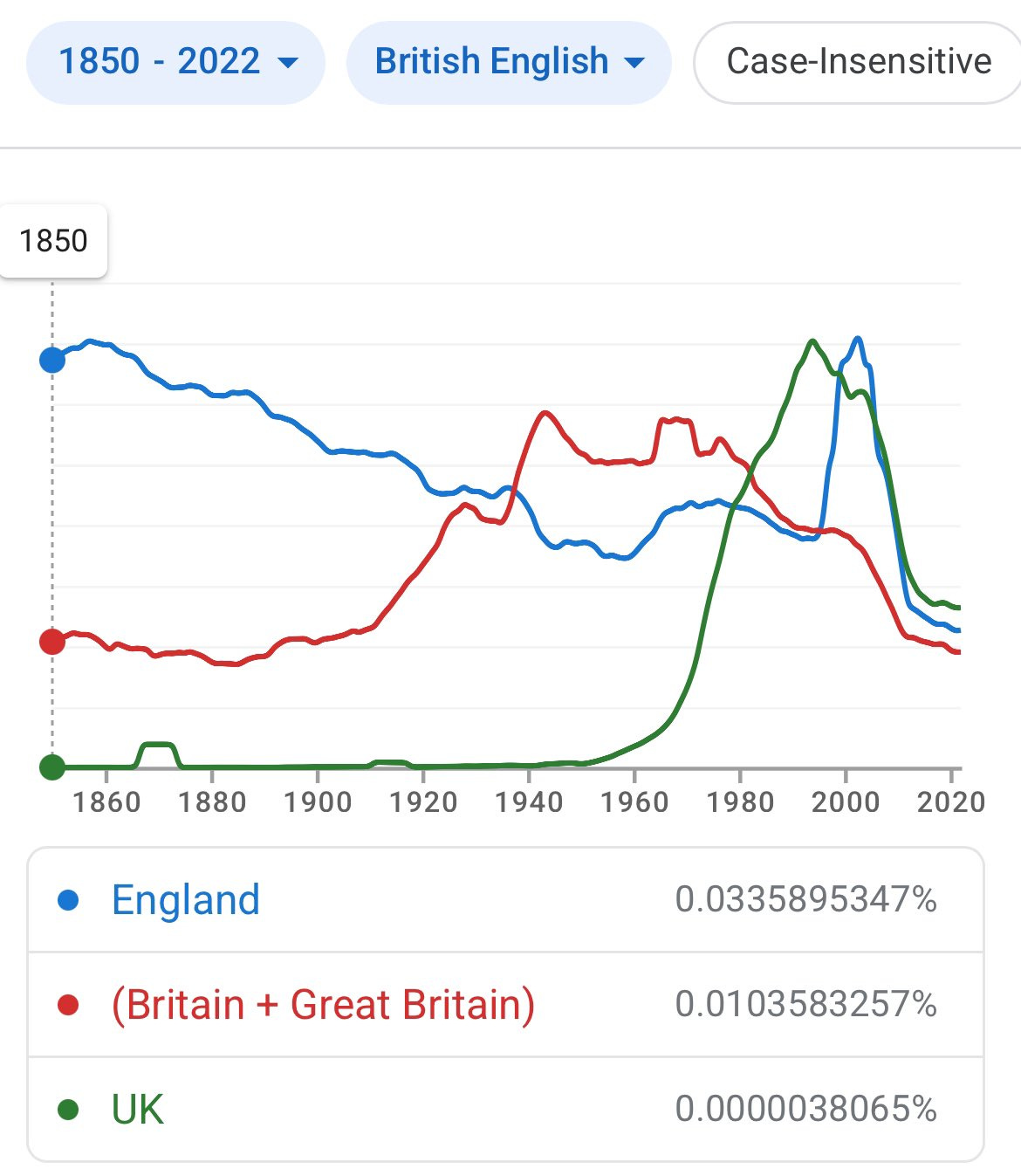

And the latter point, I think, explains the recent revival in English symbolism. Although “Britishness” isn’t definitionally a civic, open identity, it increasingly became one in the 20th Century — even before the end of Empire and recent waves of mass-immigration — in a way an ethnic identity like Englishness never could. A Google Ngram investigation tells an interesting story about the historical uses of “England”, “Britain”, and “UK” — firstly, that there was a shift toward British identification and away from English at the outbreak of World War 1, as the Union called on all its constituents to provide bodies for the war effort.

There is another, more dramatic shift in the post-War period. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, use of the term “UK” appears. This sharp rise in the 1970s coincides with the beginning of The Troubles, when the political legitimacy of the union of Britain and Northern Ireland came into focus, and declined again after the Good Friday Agreement of 1997 put a bookmark in that question in most Briton’s minds. Yet now, the “Yookay” is seemingly undergoing a resurgence in post-Boriswave Britain, the catch-all civic identifier for anyone living in the Union.

Though historically understood as an extension of English identity, Britishness was primarily expressed as a loyalty to institutions and political arrangements rather than to a people. This made it fragile as a source of loyalty and left it vulnerable to denationalisation, allowing it to be reframed in the late twentieth century as a multiracial, elective identity. Britishness has always functioned less as a nation than as a civic umbrella. Its symbols and oaths point to a sovereign rather than a nation. Rule Britannia exalts empire and liberty, and the national anthem pledges loyalty not to a people or culture but to the monarch who presides over the Union. Britain’s monarchy has implicitly welcomed every step of the country’s multiracial transformation. It now exists only as a relic of tradition, which conservatives feel obligated to rally around even as the royal family shows time and again to be decidedly on the side of anti-national forces.

In this context, Scruton’s observations take on renewed urgency. England, he argued, needs a political recognition of its own identity, not just as part of a wider Union but as a distinct nation with historical, cultural, and political coherence. Even if not articulated, many nationalists in England are returning to their national flag away from an increasingly abstract Britishness. A former advisor to Tony Blair complained on BBC Newsnight that the emergence of the St. George’s flag is “being used to racialise political discourse.”

Though not every member of the establishment will be that explicit about it, It is evident that the establishment is on shakier ground deconstructing the ethnic basis for Englishness than it is in redefining the UK. A perfect illustration of this dynamic was the now-famous clash between Thomas Skinner, happily waving a St. George’s Flag, and a seething, frothing-at-the-mouth skintellectual Narinder Kaur, who inisted men like Skinner drop their national identification for her civic conception of Britishness. The exchange captured the fault line Scruton foresaw two decades ago, now crystallised: between a rooted national identity and a hollow civic label.

A final reason to favour the end of the Union would be what it could mean for nationalism in each newly independent country. It is a constant source of frustration to nationalists to see that popular national independence movements like that of the Catalans tends to be so left-wing, and even supportive of multiracialism in a way that is clearly opposed to nationalism. The same phenomenon can be observed with the dominant independence movements of Scotland and Wales, which has also pushed British politics leftward.

But a breakup of the Union could seriously undermine this phenomenon of left-wing nationalism. The leftward character of Scottish and Welsh nationalism has chiefly arisen from their status as peripheral nations, framing themselves as smaller, historically marginalised peoples resisting domination by the English-dominated centre. Once Scotland or Wales achieves full independence, that foundational narrative disappears. No longer defined by subordination to a wealthier centre, these nations would be forced to define their national identity on new terms, and the ideological coherence of their left-wing nationalism could be weakened. As their ruling parties continue to champion multiracialism and align with globalist governance structures, they could face a challenge from a newly empowered national-populist right, currently constrained by the electoral system and the binary choice between independence movements and Unionist British parties.

In conclusion, the breakup of the Union could redefine nationalism across the former Union’s nations, allowing the emergence of a more confident English ethnic nationalism and potentially dismantling left-wing dominance on the Union’s Celtic fringe, fostering a new era of authentic national expression. In this light, the establishment’s discomfort with the St. George’s Cross reveals their intuitive understanding that what they are witnessing is not just a passing social media fad, but the first signs of their own obsolescence.

This article originally appeared on Keith Woods’ Substack and is republished by The Noticer with permission.