Claudia Hillebrand, Cardiff University

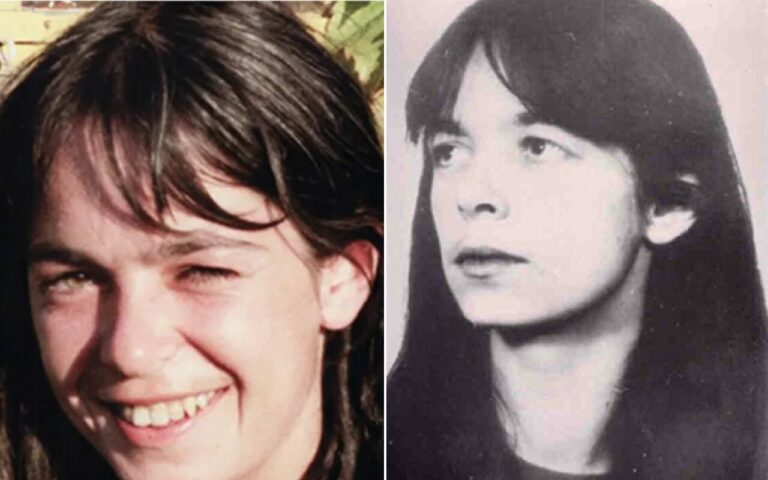

One of three long-time fugitive members of the German far-left militant organisation Red Army Faction (RAF) – better known as the Baader–Meinhof Group – has been arrested in Berlin. The now 65-year-old Daniela Klette, who was living in the German capital under the false name Claudia Ivone, is assumed to have gone underground at the end of 1989. She is thought to have participated in three terrorist attacks between then and the RAF’s disbandment in 1998.

Together with two remaining fugitives, Ernst-Volker Staub and Burkhard Garweg, Klette is accused of attempted murder and 12 robberies between 1999 and 2016 – activities aimed at keeping the group afloat.

German interior minister Nancy Faeser celebrated the arrest as being down to “decades of tireless investigative work” and as evidence of the “perseverance and staying power” of state officials. Yet the more common response to Klette’s arrest has been surprise at how she managed to live in a lively area of Berlin without being arrested.

This feeds into wider confusion about why the government’s overall efforts have not yet closed the chapter on a dark period in Germany’s recent history.

Extreme violence, extreme silence

According to the German Federal Prosecution Office, the RAF murdered 34 people and injured many others as part of its campaign for radical socio-political change that began in 1970. Despite limited public support from the beginning, the RAF was considered a considerable threat by the German state.

The RAF showed organisational flexibility with a structure and leadership that evolved over time. Klette, Staub and Garweg are assumed to be members of the brutal “third generation” of the RAF, which focused on activities against the military-industrial complex. Among other crimes, the group claimed responsibility for the 1985 murder of Ernst Zimmermann, the CEO of the Motoren and Turbinen Union (MTU), which delivered engines for battle tanks and combat planes.

Few traces were left behind at the RAF’s crime scenes, however, and the murders associated with the group remain largely unsolved. Those RAF members who have been convicted typically reveal very little, even when in custody – especially not the identity of other members.

Klette’s arrest is a reminder that tracking down terrorists can take a long time. Thorough police work can be fundamental – and the downfall of the RAF’s first generation is often seen as an example of that. Significant arrests were made in late 1970 and 1971. From January 1971, the manhunt was centrally coordinated through a special Baader-Meinhof federal police unit, which adopted innovative profiling techniques and computerised datasets.

Public assistance can also be crucial. In 1972, police officers in Hamburg were able to arrest RAF member Gudrun Ensslin in a clothes shop after the shop assistant had found a gun under Ensslin’s coat and called the police. Only after taking her fingerprints at the station did the officers realise that they had arrested one of the most wanted fugitives in Europe.

Under the radar

Klette’s case also shows that living on the run after a career in terrorism is not a glamorous existence. At best she appears to have been living an “ordinary” life, hiding in plain sight in Berlin, where she gave maths tuition, attended sports sessions and sometimes chatted with neighbours. But she also committed a number of armed robberies over the years to support even this life. The authorities found a machine pistol, an anti-tank weapon and a Kalashnikov rifle in her flat, and she was described last week as an ongoing “threat to public safety and order”.

How could Klette have stayed under the radar in Berlin for for so long – and why have Staub and Garweg continued to evade capture? It is difficult to understand why German authorities have struggled to solve so many of the crimes associated with the RAF over the years. Victims of attacks committed by the RAF and their family members have long called for better public information about investigations, perpetrators and institutional failures. But it’s not even clear how many investigators the BKA has instructed to track fugitive RAF members since the 1970s.

One likely explanation for the failure to capture the RAF group members lies in the tactics and modus operandi of the third generation. Terrorist organisations are learning institutions, and the third generation built resilience by absorbing important lessons about secrecy from earlier RAF generations. It is assumed that not all members of the third generation are even known about.

It has also been suggested that the male-dominated security institutions have failed to fully acknowledge the central role that women played in these campaigns of political violence – and that they therefore overlooked them. In Klette’s case, it has emerged that journalists identified her with the help of AI tools as long ago as November 2023. Why police failed to arrest her – or decided not to arrest her – until the end of February 2024 is puzzling.

The RAF never managed to shake Germany’s democratic order in any seriousness but Klette’s case is a reminder that the story of far-left terrorism is not over, decades later. Culprits are still on the run and potentially still committing violent crimes to fund their existence – and many questions remain unanswered.![]()

Claudia Hillebrand, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.