The following was written as an introduction to Keith Woods’ book Irish Nationalism: Essential Writings, and is republished by The Noticer with permission. Please consider purchasing the book and leaving a positive review.

Human settlement in Ireland began around 8000 BC, during the Mesolithic period, after the retreat of Ice Age glaciers. Archaeological evidence indicates that small groups of hunter-gatherers arrived by sea from Britain or western Europe. These early inhabitants relied on fishing, hunting, and gathering, establishing temporary camps that left little impact on the archaeological record. Their population remained small, limited by the resources available on the small island, until the Neolithic period introduced significant change.

By 4000 BC, farming communities from Britain and Europe arrived, replacing or blending with earlier hunter-gatherers. Coming to Ireland from Britain and continental Europe, these settlers brought domesticated animals, cereal crops, and pottery. They constructed megalithic structures, including Ireland’s iconic passage tombs like Newgrange and Knowth in the Boyne Valley, proof of complex ritual practices and organised societies. This migration established Ireland’s first substantial population base, laying the groundwork for later demographic shifts.

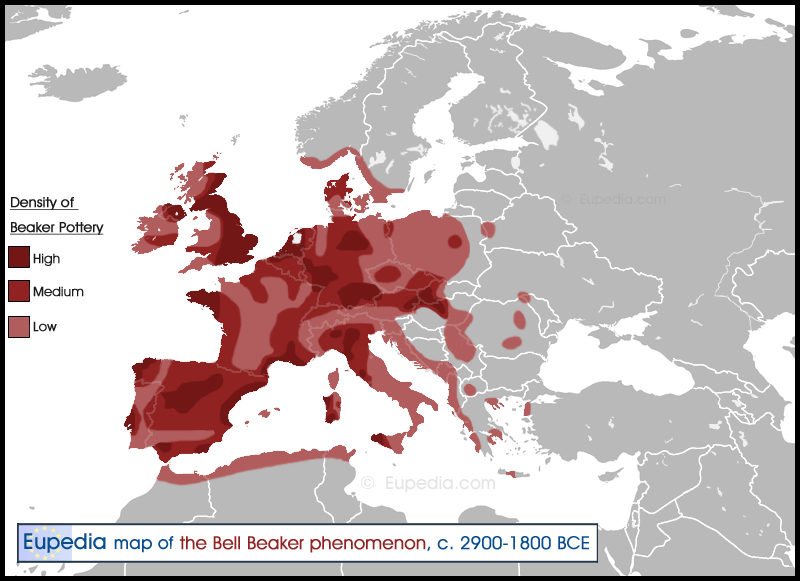

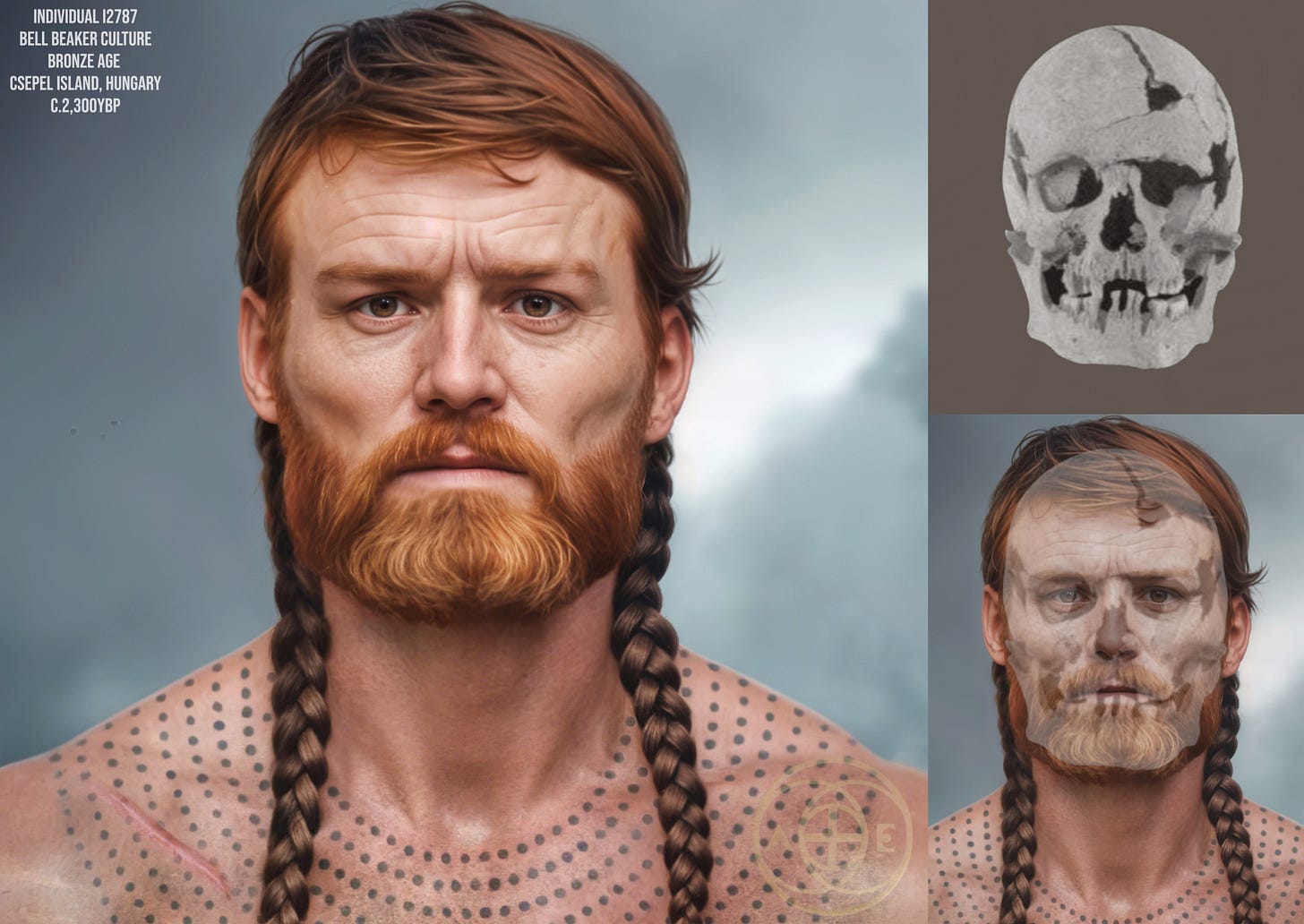

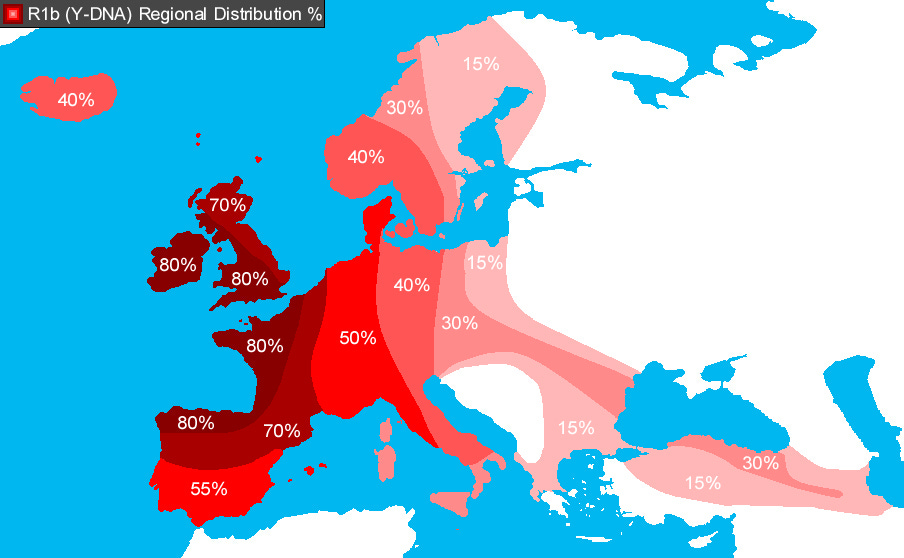

The Bronze Age, beginning around 2500 BC, saw another major population movement associated with the Bell Beaker culture, which most likely took the form of a violent invasion. Named for their distinctive bell-shaped pottery vessels, Bell Beaker folk likely originated in the modern day Low Countries. As well as their distinctive pottery, they brought with them advanced metalworking and mining techniques, leaving traces like the copper mines at Mount Gabriel in County Cork. Their impact is perhaps most striking in their burial practices, seen at Tara, where single inhumations replaced earlier traditions. At this sacred site, archaeologists have uncovered individual graves containing bodies carefully interred with grave goods like pots and jewellery, signalling a new reverence for personal status and the afterlife. This kind of burial practice is a marker of Indo-European peoples, and the Bell Beaker culture was one successor to the so-called “Yamnaya culture” of the early Proto-Indo-Europeans. Genetic studies show a significant influx of new Steppe-related DNA entering Ireland during this period, reflective of a transformative migration of Indo-European people.

This new population wave, peaking around 2400 BC, coincides with a near-complete replacement of the earlier Neolithic gene pool in Ireland, suggesting that this ancient invasion almost completely displaced the prior Neolithic populations, who were likely no match for the expansive Bronze Age warriors. The Bell Beaker arrival totally reshaped Ireland’s population and material culture, and provided the genetic stock of the island that has changed little since, isolated from other major population movements on the continent. This population transformation also brought an expansion of trade networks, connecting Ireland to a wider Bronze Age culture in Britain and the continent.

It is with the Iron Age, starting around 600 BC, that we see the introduction of Celtic culture to Ireland, evident in the spread of La Tène-style artifacts such as iron tools and hillforts.

It was once believed this cultural shift was brought by a Celtic invasion of Ireland, but we now know there was in fact a very stable continuity with earlier Bronze Age populations, showing little sign of a major new influx. Instead, it seems Ireland’s native inhabitants adopted Celtic language and practices through cultural diffusion, likely coming via elites who encountered Celtic culture through trade and contact with Celtic-speaking regions in Britain. It was in this period that the Irish Gaelic language emerged as dominant, giving the island’s inhabitants a more distinct cultural identity. Ireland had always been divided politically, with sovereignty fragmented among many local chieftains governing small kingdoms or túatha. Yet by the Iron Age there was a distinct people and language in Ireland that would change little up to the modern period.

The adoption of Celtic culture was one major part of the creation of what is distinctively Irish culture, another was the arrival of Christianity in the fifth century AD. St. Patrick, a British-born missionary, is responsible for this conversion from paganism. Patrick, captured as a slave in Ireland before returning as a missionary, established churches and converted local leaders, achieving a full scale religious conversion of the island. The shift integrated Ireland into the wider Christian world, yet also reinforced its cultural distinctiveness, for unlike in Roman Britain, Christianity in Ireland blended much more with existing customs to create a distinctive Celtic Christianity. Monasteries adopted a decentralised structure that mirrored the túatha system. St. Patrick was revered in Irish tradition not just as a propagator of the Gospel, but also as a legitimiser of native traditions he deemed compatible with Christianity, blessing the pre-Christian Brehon Law of Ireland. In the centuries that followed, monastic hubs like Clonmacnoise became beacons of Gaelic learning, blending local traditions with Latin scholarship and helping cement a cultural cohesion around Irish identity.

During the early Middle Ages, these monasteries became renowned centers of scholarship not just in Ireland, but across the Christian world, attracting students and scholars from all over Europe and establishing Ireland as a pivotal center of education in the Latin world. Their emphasis on manuscript illumination and the preservation of classical texts helped sustain and spread knowledge during a time when most of the rest of the continent faced cultural decline. But for Ireland it was a golden age culturally, in which it earned the affectionate title of ‘the land of saints and scholars’, and in which Irish monks produced some of the finest artefacts of medieval Christian art in the form of high crosses and illustrative manuscripts like the renowned Book of Kells.

Politically, Ireland remained fragmented, but the concept of the High King (Ard Rí) reflects an early sense of an Irish political unity. Dating back to at least the fifth century, the High King was a ceremonial overlord, claiming authority over regional kings from the sacred site of Tara. Medieval Irish literature portrayed an unbroken line of High Kings ruling Ireland from the Hill of Tara that stretched back thousands of years. In practice, this title was contested, with rival dynasties like the Uí Néill in the north and the Eóganachta in the south vying for dominance. The Annals of Ulster and other texts record these struggles, showing that while the High King lacked centralised power, the existence of the position symbolised a shared aspiration for unity. Although this is something quite distinct from modern idea of nationalism, it does indicate a recognition of Ireland as a single entity, even if this was always tenuous politically.

Beginning in the late eighth century, Ireland became a center of the Viking Age. Norse raids began targeting Ireland’s rich monasteries and other settllements, before Vikings established permanent settlements like Dublin, Wexford, and Waterford by the ninth century. These coastal enclaves introduced trade and urbanism, linking Ireland to existing Scandinavian networks. The Vikings came as hostile invaders, but over time they often assimilated, adopting the native language and intermarrying with the native population. The Norse presence also intensified regional conflicts, as local kings often chose to ally with them over their regional enemies.

The tenth and eleventh centuries saw efforts to assert greater political control over all of Ireland, exemplified in the rise of Brian Boru. A member of the Dál Cais dynasty from Munster, Brian challenged Uí Néill dominance, consolidating power through military campaigns and alliances. In 1002 AD, Brian claimed the High Kingship of Ireland. Inspired by Julius Caesar, he styled himself Imperator Scottorum: Emperor of the Irish. His victory at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 AD against a combined Viking and Leinster force cemented his legacy, though he was killed in the battle. Brian’s death fragmented his coalition, and no successor ever matched his scope. But his reign did mark a symbolic peak in the idea of Irish unity, drawing on Gaelic traditions and Christian legitimacy to project a proto-national vision, even if it remained yet unrealised.

Norman rule in Ireland began in 1169, initiated by the invitation of Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster. Led by Richard de Clare (Strongbow), the Normans brought their distinctive feudalism, today most visible in the many Norman castles dotted around Ireland. Initially allies of local rulers, they soon established lordships, particularly in Leinster. As with the Norse invasions, over time many Anglo-Normans assimilated, adopting Gaelic customs and language and marrying into the native population. “More Irish than the Irish themselves” (Níos Gaelaí ná na Gaeil féin) was a phrase that became common in Irish historiography to describe this common trend of assimilation. The English Crown, alarmed by the trend, imposed the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366 which banned settlers from speaking Irish or marrying natives. However, the statutes had little impact, and the Hiberno-Normans continued to assimilate to the dominant Irish cultural identity. Outside of The English Pale, an area encompassing modern Dublin and surrounding areas, Gaelic and Norman-Irish lords retained a great deal of autonomy from the British crown. This period solidified a dual identity: a native Irish core, now Christian and Irish-speaking, alongside a partially integrated foreign elite.

The sixteenth century marked a turning point with the Tudor conquest, as England sought to impose centralised authority over all of Ireland. Henry VIII declared himself King of Ireland in 1541, introducing the “surrender and regrant” policy, which required Gaelic lords to submit to English rule in exchange for retaining their lands under feudal titles. Many complied formally but preserved traditional practices, limiting the policy’s effectiveness and still frustrating the British Crown’s desire to fully entrench British rule over Ireland. The Reformation, initiated by Henry and enforced under Elizabeth I, only deepened divisions. Most Irish rejected Protestantism, in large part because of its association with English dominance, meaning that Catholicism emerged as a marker of resistance and became more central to Irish identity.

The persecution of Catholicism also forced closer alliances between many of the “Old English” who had maintained their Catholic faith, and now felt greater affinity with their Irish neighbours. Better educated than the native Irish, many became great opponents of the reconquests of Ireland from the Tudor era on. One example is the historian Geoffrey Keating, born to a Gaelicised Old English family in Tipperary in 1580. Keating was termed ‘the Herodotus of Ireland’ for gathering old Irish manuscripts and oral traditions and ordering and archiving them to safeguard their existence from the collapse of the old Gaelic tradition. The culmination of this project was his major work, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (The History of Ireland), which became widely popular among the educated in Ireland and led to a stronger sense of a shared national identity.

Elizabeth I’s reign saw military efforts to suppress opposition, including the Desmond Rebellions (1569–1583) and the Nine Years’ War (1594–1603). The latter, led by Irish lords Hugh O’Neill and Hugh Roe O’Donnell, was a serious blow at English power in Ireland. The Irish confederacy drew in thousands of fighters, captured most of the island, secured a string of military victories, and secured military aid from Catholic Spain. However, the English secured a vital victory at the battle of Kinsale in 1601, turning the course of the war. The Flight of the Earls in 1607, when O’Neill and other leaders fled to Europe (after news of another planned rebellion reached British authorities) signalled the final collapse of the political order of Gaelic Ireland. The Plantation of Ulster followed, beginning in 1609, with land confiscated from Catholic owners and granted to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland.

The seventeenth century further solidified English control. In response to ongoing land dispossession by an increasingly aggressive Protestant regime, the 1641 Rebellion saw Gaelic Irish and Old English Catholics unite against the encroaching Protestant settlers. The Catholic rebels managed to seize two thirds of the country, with Royalist forces only holding Dublin, Cork and surrounding areas, with some Protestant militias holding parts of Ulster. Out of the captured territory, the rebels formed the Irish Catholic Confederation, with its government based out of Kilkenny. Irish self-government over so much of the territory of Ireland, and reports of atrocities committed against Protestant settlers, prompted a severe response in the form of Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland, beginning in 1649.

The result of Cromwell’s brutal campaigns was a demographic shock — as much as 20% of the Irish population died in this period to war, famine and plague — and a drastic reduction in Catholic land ownership to the benefit of Protestant settlers. The Penal Laws, introduced after the Williamite War (1689–1691), restricted Catholics and non-Anglican Protestants from political participation, landownership, and education. These measures established the Protestant Ascendancy, a minority ruling class aligned with Britain, which generated widespread and longstanding discontent among the excluded population. By this stage, Irish identity began to reflect more a shared experience of subordination and resistance, as the many failed attempts of the native Irish to break the English yoke creating, through generations, a romantic canon of Irish nationalist struggle.

In the eighteenth century, Ireland functioned as a subordinate kingdom within the British system, governed by a Dublin Parliament that served the Ascendancy’s interests. Economic policies restricted trade, and the Penal Laws continued to marginalise Catholics and Presbyterian Dissenters. The native Irish, reduced to tenant farmers, faced growing hardship, while the Old English Catholic gentry had also lost influence. In Ulster, Presbyterians, though Protestant, encountered discrimination from the Anglican establishment, fostering resentment. The Enlightenment brought ideas of popular sovereignty and individual liberty to the educated in Ireland, as well as a spirit of revolutionary zeal, influencing young idealists in urban centers like Dublin and Belfast. The American Revolution’s success in removing British rule further inspired Irish nationalists. The Irish Volunteers, formed in 1778 as a militia, became a political force, securing the Constitution of 1782, which increased parliamentary autonomy. However, this body remained under British control and excluded non-Anglicans, failing to address broader grievances.

The Society of United Irishmen, founded in 1791 in Belfast by figures like Theobald Wolfe Tone, emerged in this environment. The group drew on French Revolutionary ideals, but initially sought peaceful parliamentary reform, including an expansion of the vote and Catholic emancipation. It aimed to unite Ireland’s religious communities under a shared national struggle against British rule. It was here that the Irish national struggle became wedded to the ideals of Republicanism, a political ideal under which the country would eventually unite for its national independence struggle in the 20th century. But this was just the political form — by this time, there was a clearly distinct Irish people, culture and identity with roots stretching back to the ancient world.

From the hunter-gatherers who first tread its shores to the Gaelic-speaking Christians who resisted centuries of conquest, Ireland’s story is one of resilience. Across millennia, waves of migration, cultural diffusion and differentiation, foreign incursion and resistance forged a unique people with a rich culture. The Tudor conquest and subsequent English domination hardened this identity, binding it to Catholicism and a romantic yearning for the ideal of an Ireland both Gaelic and free. The eighteenth and nineteenth century’s revolutionary fervour crystallised these threads into a more distinctly modern nationalist vision which, carried by the bravery and sacrifice of one of Ireland’s most heroic generations, would achieve the victories that began the end of British rule in Ireland.